You are here

Retail Indicators I. Identifying 'clone towns' across the UK

By Patrick Ballantyne

A new data product from researchers at the CDRC highlights marked differences in the diversity of retail centres across Great Britain.

Measuring retail centre homogenisation

Retail centre diversity has declined substantially, with a greater number of retail and consumption spaces being increasingly occupied by large chains, as opposed to other spaces which rely on a more diverse offer, consisting of greater numbers of independent retailers and service providers. Across Great Britain this is particularly apparent in major town and city centres, at the top of the retail centre hierarchy, and those ‘organic’ or ‘evolved’ shopping spaces, which are becoming increasingly reliant on these large chains. The resultant impact is that Great Britain remains dominated by ‘bland’ consumption spaces that are identical to each other, in terms of their retail offering, a geographical phenomenon thus far not quantified.

As part of a new set of retail centre indicators produced by CDRC researchers (1), it has become possible to unpack differences in the overall loss of retail centre diversity (homogenisation), through development of a Clone town measure for British retail centres, based on the provision of independent and chain retailers within them. The original measure, first conceptualised in NEF’s ‘Clone Town Britain’ survey (2), was designed to quantify the loss of diversity on high streets, assessing whether given locations feel more like a ‘home town’ or ‘clone town’.

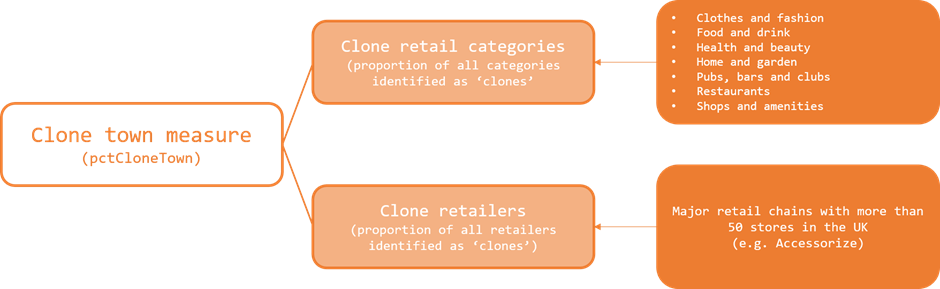

This ‘Clone town’ measure for CDRC retail centres (1) as seen on Mapmaker, the first of its kind, is calculated using data from the Local Data Company (3), to identify levels of diversity between individual tenants in a retail centre. In particular, the measure is calculated by considering the abundance of ‘clone’ retailers and ‘clone’ retail categories, as below.

The Clone town measure (pctCloneTown) can be easily interpreted; higher values reflect a greater dominance of clone retailers and clone retail categories in a retail centre (i.e. Clone town), whilst lower values reflect a more diverse, independent orientated retail centre. The measure has however not been calculated for shopping centres and retail parks (4).

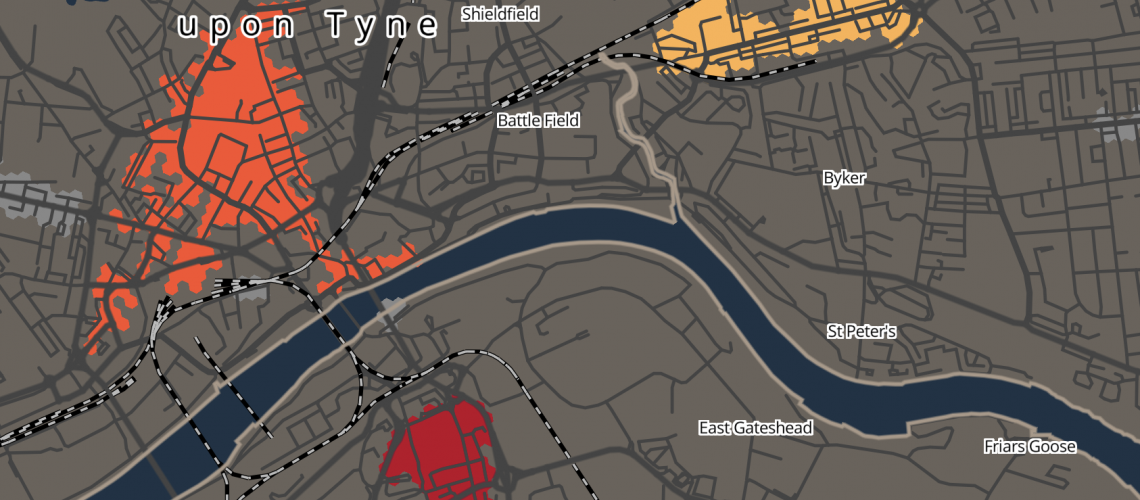

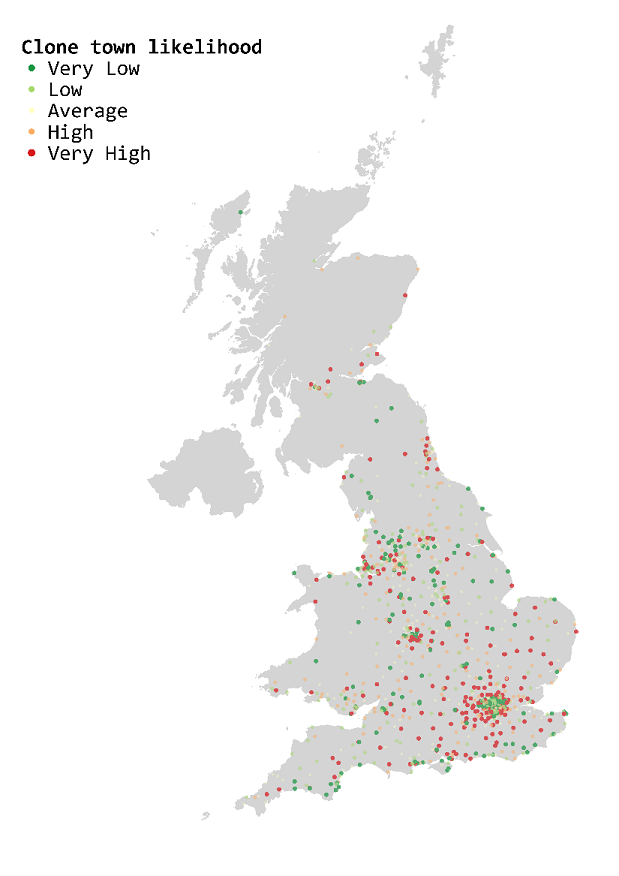

The map below shows the distribution of these scores across Great Britain. Large clusters of the most diverse retail centres (lowest Clone town scores) were found in inner city London, with some of the lowest scores seen for well-established, unique shopping destinations like Kings Road, Knightsbridge and Portobello Road. Retail centres with the highest Clone town scores were widespread, often located in the suburbs of major cities like London and Liverpool, or at the core of major town centres (e.g. Telford, Scunthorpe, Stevenage).

Identikit or Quirky?

Extracting the highest Clone town scores enables identification of a series of ‘identikit’ retail centres, as seen below in the table on the left. It is unsurprising that Telford has emerged as the most significant ‘Clone town’, as it is a rare case in which a ‘traditional’ town centre is not present; the town of Telford is orientated around a large shopping centre, containing many of the major ‘clone’ brands (e.g. Primark, Superdrug, WHSmith). This is also the case for many of the other Clone towns, such as Welwyn Garden City, Bracknell and Runcorn.

On the other hand, extracting the ten lowest Clone town scores, enables identification of the most unique, diverse and exciting centres of retail across Great Britain. Characteristic of these centres is the notable absence of well-established chains, instead comprising an abundance of independent retailers and family-owned businesses. For example, Stokes Croft in Cotham is well known for providing an excellent mix of independent shops and restaurants, and Golborne Road in London, which incorporates the famous Portobello Road Market, is often described as authentic due to its abundance of multinational shops, cafes and ‘bric-a-brac’.

Why is the Clone town measure useful?

The homogenisation of British retail centres is resulting in the dramatic loss of a sense of place, with impacts on local communities. However, as originally suggested by the NEF, there is time to limit this process, and the CDRC Clone town measure can provide supporting resources for doing so. We can now identify those retail centres on the cusp of becoming ‘Clones’, labelled ‘Borders’ in the original NEF study. These ‘vulnerable’ centres, which comprise average Clone town values (e.g. Didsbury, Belgravia) can be identified and targeted with a range of policy solutions to reverse and/or limit the process of retail and leisure homogenisation (e.g. planning laws to protect local stores).

The CDRC Clone town measure offers a unique insight to the geography of diversity loss in British retail centres. For the first time we are able to quantify the level of retail centre ‘blandness’, providing vital supporting information for policy action by organisation such as the High Streets Task Force (5), as well as providing a useful data product to support other related research projects.

Notes

1. CDRC Retail Centre Boundaries and Indicators. Available at: https://data.cdrc.ac.uk/dataset/retail-centre-boundaries.

2. NEF - Clone Town Britain: The survey results on the bland state of the nation. Available at: https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/1733ceec8041a9de5e_ubm6b6t6i.pdf

3. Local Data Company – Retail type, vacancy and address dataset. Available at: https://data.cdrc.ac.uk/dataset/local-data-company-retail-type-vacancy-a....

4. The Clone town measure is not readily available for shopping centres and retail parks, as these would yield very high values, which would be of little significance for looking at Clone towns. Values of NA are used in these cases.

5. High Streets Task Force - https://www.highstreetstaskforce.org.uk/